HALLOWED GROUND

By Jill Devine

Early last year, Jack Gray and his family were out for a walk when they noticed old headstones in the woods near the golf course at Brambleton Regional Park.

The Brambleton family had stumbled upon the remains of the Lyons Family Civil War Cemetery. Jack, 15 and a Boy Scout, had been looking for a project he could lead to earn his Eagle Scout badge. When he saw the cemetery, inspiration struck.

“We found a stone wall and, at first, didn’t know what it was. As soon as I realized that we were looking at a cemetery, I knew this would be a great Eagle project for me,” said Jack, who after doing some research set out to restore the cemetery with the help of his troop and other volunteers. “I knew I was looking at a piece of history, right here in our neighborhood.”

Jack had found what so many others in Ashburn have also discovered — there is history all around us in the form of old cemeteries. Many are small family plots, dating to Ashburn’s farming days, often sitting in plain sight in the most unusual places.

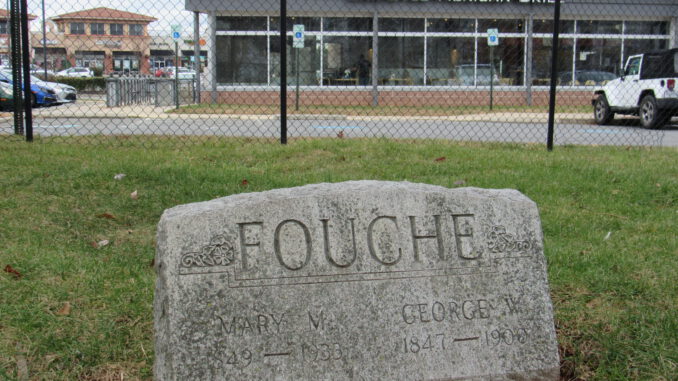

Take the tiny cemetery tucked between busy Shellhorn Road and the Chipotle restaurant at Ashburn’s Shoppes at Ryan Park. It seems so out of place – one lonely grave, separated from a parking lot and a Giant grocery store by a small patch of grass and a chain link fence.

The single headstone honors husband and wife George (1847–1900) and Mary (1849-1933) Fouche, who were buried in a family cemetery on land owned for generations by George’s ancestors. According to newspaper obituaries, George was a “well-known citizen” who died of pneumonia, and when Mary died at age 84, “many gathered to pay her tribute.” There may be other unmarked graves at the site as well, but George and Mary’s children were buried at town cemeteries in Leesburg and Herndon.

Steve Thompson, an archaeologist for Loudoun County’s Office of Planning and Zoning, said the Fouche gravesite is just one of 219 cemeteries currently identified in a Loudoun County database. Almost 20 of those are in or near Ashburn. That list will probably grow.

“Previously unrecorded cemeteries continue to be discovered through the land development applications process, while others are reported by county residents,” Thompson said.

SPREADING DEVELOPMENT

Since bulldozers first arrived in rural Ashburn in the 1980s, developers have struggled to work around the old community’s numerous small cemeteries. All gravesites are protected under Virginia law, but developers’ solutions have sometimes been less than ideal.

Some are strangely close to homes — such as the French/Bradshaw Cemetery in Loudoun Valley Estates. Others are wedged against retail centers — like the Craven Cemetery near the CVS Pharmacy by Farmwell Road. And some, sadly, are left to fade away in the woods — such as the Etcher Cemetery, on private property off Sycolin Road, near the entrance to the Academies of Loudoun.

When land is sold in Virginia, the buyer becomes the owner of any graves on the property, except in rare cases when family members retain ownership of graves through a deed. As long as the graves are not disturbed, owners are not obligated to maintain gravesites in any way. They must provide access for descendants or researchers to visit, although they can require visitors to make an appointment to do so. If development is planned near known graves, the owner must try to locate and notify descendants and must follow county requirements regarding cemeteries.

It is a felony to knowingly disturb human remains. Developers will search records and conduct history and physical archeology studies of the entire property before construction can begin. “The difficulty is that gravesites are not always readily apparent,” Thompson said.

TIME TAKES ITS TOLL

While some families could afford headstones, many graves were marked only by field stones or wooden markers that have long since decayed. This presents a dire situation for many gravesites, especially those of thousands of African Americans who were enslaved at Loudoun plantations, because they were almost always buried in remote areas marked by only a stone or nothing at all, making them difficult to discover.

Sometimes the only clues are depressions in the ground or the presence of non-native groundcovers or flowering plants.

“Almost certainly some gravesites prior to the 20th century have been developed over if there is no lasting record of them in the county property records and surface indications of unrecorded cemeteries was not seen during development,” Thompson said.

PRESERVING FAMILY PLOTS

State law allows landowners to relocate graves, Thompson said, but that requires a court order and is not common, primarily due to public opposition and the associated costs.

To accommodate the Route 28/Nokes Boulevard interchange project in 2007, the Virginia Department of Transportation spent $100,000 relocating as many as 40 graves, some more than 200 years old, from a Loudoun site known as the Kilgour/Hummer Cemetery. Most of the graves were moved to Herndon’s Chestnut Grove Cemetery, including those of George Kilgour, a mill operator who owned the land in the early 1700s, and his wife, Martina.

In 1996, to expand a runway at Washington Dulles International Airport, the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority relocated 28 marked graves, dated from 1871 to 1985, from the McCullock/Moran/Stallion Cemetery, with almost all going to Chestnut Grove at the request of descendants.

Fairfax Genealogical Society records list four other cemeteries that were relocated during the airport’s construction in the late 1950s, and local historians speculate that other cemeteries, unknown to the FAA at time of development, could lie under the airport’s buildings and runways.

RESPECT AND HONOR

Nineteenth-century British prime minister William Ewart Gladstone once said that how a community treats its dead is a good indicator of how it treats its living. How is Ashburn doing? Thanks to county and volunteer efforts, better than before.

Broadlands resident Jim Wiesemeyer, an agricultural journalist, said the Broad Run Church Cemetery (also called Hillside), in his backyard off Waxpool Road was a big selling point when he bought his home in 1997.

“This area was once dairy cattle country, so the cemetery went straight to my heart as a testimony to the cattle industry producers who lived here,” he said.

Both he and his neighbor, Catherine Boone, said they feel protective of the cemetery, which is visible from their back windows.

“My own children are comfortable with the cemetery being there, but I’ve taught them to respect it and not pass the fence without me,” Boone said. “And I do keep a watchful eye when someone enters the area.”

Both neighbors agree that deterioration is part of a cemetery’s lifespan, although Wiesemeyer said it would be nice to see the groundhog holes — common in many cemeteries — filled and the headstones repaired.

COMMUNITY EFFORT

It was that kind of need that motivated Jack Gray to fix up the decrepit Lyons Family cemetery at the Brambleton golf course. One of Jack’s first steps was to meet with Northern Virginia Parks Authority Manager Dustin Betthauser to gain permission to work on the site.

Jack’s father, Bart Gray, said they were aware of public and cultural sensitivity concerning gravesites, so he wanted to make sure his son would not unwittingly encroach on gravesites of undiscovered enslaved African Americans. Before starting work, they followed careful guidelines while searching areas outside of the 4,200-square-foot cemetery.

The project included adding landscaping, restoring a stone fence and a wrought iron fence, cleaning, repairing and restoring grave markers, and updating archives and signage. Jack consulted with Jim Short, whose company, Graveside Guardians in Manassas, specializes in the preservation of cemeteries. COVID-19 restrictions presented an added layer of difficulty in terms of social distancing, but 25 hard-working volunteers completed the physical portion of the project in one day.

“Many people stopped to thank us or give us fist bumps — golfers, veterans, people walking by,” said Jack, who successfully earned his Eagle rank in December. “It felt good.”

Jill Devine is a freelance writer and former magazine editor from Loudoun County who writes for a variety of Virginia publications.

BELMONT ENSLAVED CEMETERY

In 2015, Pastor Michelle Thomas, a Lansdowne resident, was searching for a place to build her church when she noticed an African American cemetery on the map, near the southeast corner of Route 7 and Belmont Ridge Road. Visiting the site, she had to cut through the forest before finding the forgotten markers of those enslaved at nearby Belmont Plantation.

“I wasn’t expecting them to be laid to rest in such a beautiful location,” Thomas said. “Our ancestors were laid to rest in a prime location, where we can now study their path for years to come. This place is proof of their existence and a testimony to their resilience and struggle for freedom.”

Thomas is president of the Loudoun’s NAACP Branch and founder of the Loudoun Freedom Center. She is also a former engineer who returned to school for a certificate in public history and historic preservation at Northern Virginia Community College. With the help of volunteers, Thomas has helped bring dignity and honor to the memory of Loudoun’s enslaved, who she says constituted as much as a quarter of Loudoun’s population before emancipation.

Thomas was able to persuade the owners of the land — home building company Toll Brothers — to donate the land to the Loudoun Freedom Center to preserve the cemetery and ensure that it would be open to the community. Toll Brothers also recently announced plans to develop neighboring land and is working with the Freedom Center to expand the center’s property to provide room for a future museum and history trail. “Now African Americans actually own a part of this slave plantation where [their ancestors] had been forced to work — a strange bit of irony,” she said.

In 2018, as an Eagle Scout project, Mikaeel Martinez Jaka from Troop 2019 in Leesburg led about 100 volunteers to build a gravel path to the cemetery, making it possible for visitors to safely access the site and learn its history.

“I felt it was so important to help increase public awareness of the history and effects of enslavement on the African American population,” Jaka said.

Loudoun historian Wynne Saffer, who once chaired a committee on historic cemeteries for the Thomas Balch Library in Leesburg, believes African American cemeteries should be protected by federal laws similar to Native American gravesites. “It is hard to advocate for the gravesites of those who have no records, because it is impossible to search for their descendants who would be necessary for appeals in court.”

Sadly, last year, Thomas buried her 16-year-old son, Fitz Alexander Campbell Thomas, at the cemetery after he died in a swimming accident. He was the first African American person who was born free to be buried there. “I wanted to bury him in the place that is dear to my heart,” she said.

— Jill Devine

VISITING CEMETERIES

In 2019, Loudoun’s Office of Mapping and Geographic Information launched an online interactive map of known Loudoun cemeteries (https://tinyurl.com/6sa22mtz). Burial sites are color-coded as active, inactive or disturbed/removed. Using the map, it is easy to find most of the gravesites near Ashburn. Before visiting, be aware of laws concerning private property and the treatment of human graves. Ask permission to enter if required, and do not remove, alter or adjust anything on or near graves, including rocks, stones or bricks.

Each grave, whether that of a plantation owner or an enslaved laborer, a dairy farmer or a child lost at birth, is part of Loudoun’s heritage.