FORGING AN IRON PATH

By Mathew Annis

Across Ashburn Road from the Carolina Brothers barbecue restaurant, there is a broken rock face – 15 feet of shale, in summer choked with brambles and honeysuckle.

Hard to believe – as cyclists and joggers pass by and as families tuck in to pulled pork sandwiches just a few yards away – but this jumble of rock is evidence of a remarkable and transformative feat of engineering that would not be surpassed for 100 years – the coming of the railroads.

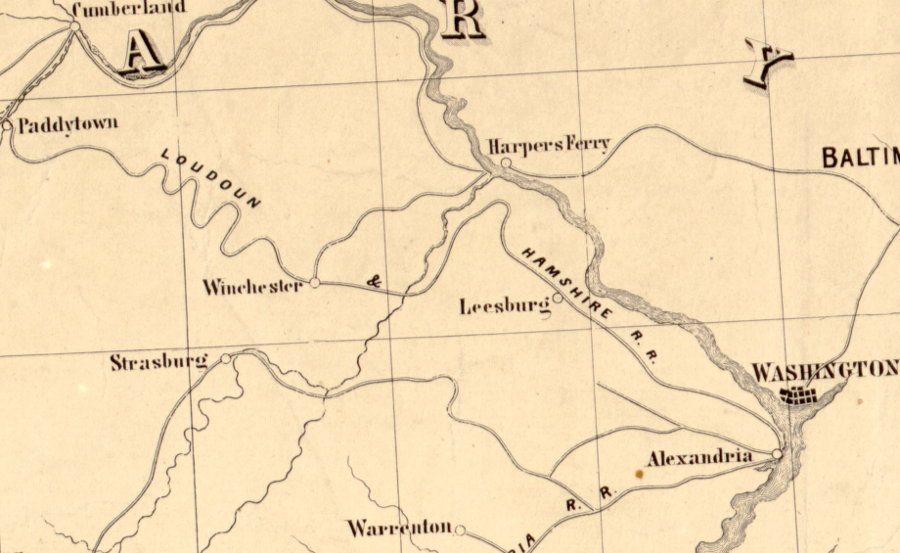

The first sign of this transformation came in late 1853, when a surveying party appeared at the banks of the Broad Run. This was the first step in a bold new venture – the Alexandria, Loudoun and Hampshire Railroad, connecting the port of Alexandria with the western Virginia coalfields.

The AL&H Railroad would later become the W&OD Railroad, the namesake of the famous trail that runs through our community.

The railroad surveyors made their often tortuous way across what is now Ashburn before crossing the Goose Creek and continuing west. Tortuous because the railroad’s path through Loudoun crossed several waterways and went nowhere near any existing major roads. The surveyors would have been forced to scramble along muddy farm tracks and across fields and to ford fast-flowing creeks.

Armed with the surveyors’ reports, railroad construction began in February 1855, according to Ames W. Williams’ 1977 history of the line. Around Ashburn, then known as Farmwell, the biggest obstacles were likely the crossings of Broad Run and Goose Creek. And while the true engineering challenge lay in the distant Blue Ridge, the terrain of the Virginia Piedmont presented its own difficulties.

Unlike a road, which could snake over hills and down valleys, a rail locomotive needs smooth gradients on which to run. Even a bump of a few feet was an obstacle too great for rails to cross and needed to be smoothed out.

This grading process formed the bulk of the work. Higher terrain – like that opposite Carolina Brothers – had to be cut through. Workers with shovels and picks cleared the soil and loose rock. Where there were larger rock formations, gunpowder was used to blast the rock into smaller pieces, which could be carted away.

Lower terrain, on the other hand, had to be raised. The grading process here involved building embankments – long earthworks – that could connect the higher ground on each side and support the rails, like the section just east of Ashburn Road next to Carolina Brothers.

Perhaps the greatest challenges were those river crossings. These required skilled workers with experience building masonry structures. At each side of the Broad Run and at Goose Creek, stone abutments were built before bridges finally spanned the rivers.

But describing the process built barely does justice to the work involved.

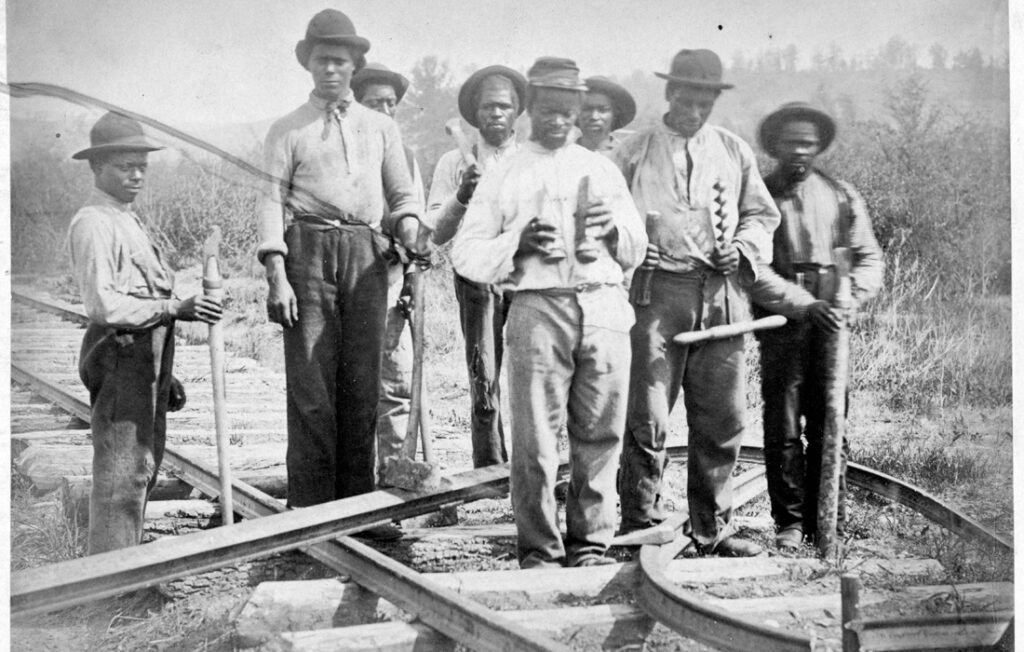

“The AL&H Railroad was built primarily using hand labor,” said Paul McCray, official historian of NOVA Parks. “While they had drags for loosening soil and wagons to move it, much of the work depended upon men with shovels to cut down the hills and fill the low areas. Arches, culverts and bridge-supporting structures were built by masons using block and tackle to hoist stones sometimes more than 50 feet in the air.”

We can imagine the gunpowder blasting its way through the rocks and the laying of trestles across the swift flowing waters of Goose Creek. We can imagine the gangs of hundreds of laborers shoveling their way across Northern Virginia, mile by mile. But whose hands gripped the shovels and picks? Whose hands built the masonry and laid the bridges?

Many Southern railroads were built using enslaved labor, hired from local landowners along the route. Was the railroad through Loudoun built the same way?

The answer is frustratingly uncertain. Many of the records of the railroad are long gone – lost or destroyed – and what survives is largely silent on the subject. But while we may not know the identities of everyone who worked to build the railroad, we do have a few clues as to the identities of some.

First is an article in Leesburg’s Democratic Mirror newspaper from Oct. 31, 1860. Buried amongst news of the upcoming election, just three sentences tell of a fatal accident.

“An Irishman, whose name we did not learn, was killed on the A. L. & H. Railroad, about four miles above Leesburg,” the article reads.

Railroad building had passed beyond the Ashburn area by the fall of 1860 and had reached Clarke’s Gap, where the reported accident likely occurred.

Another piece of evidence is census returns from the same year. While the newspaper article mentions just one Irishman, in the official census count, there are dozens. Patrick Maharney, Thomas Flanagan, Daniel Buckley, John Coughlan and almost 30 more. All born in Ireland, all laborers and all residing at the same location near Leesburg in August 1860.

At their head was James McWilliams – another Irishman – living at the same site with his family, his occupation listed as “Railroad Contractor.” Thus, the census record seems to mark the camp of a railroad construction crew, almost certainly the same men who had worked their way to Clarke’s Gap from the Ashburn area over the previous year.

What brought these men 3,000 miles to work on a Virginia railroad was the most pressing of reasons – survival.

Fifteen years earlier, the Irish countryside had witnessed the onset of the potato blight, which decimated Ireland’s food production and sent more than 2 million refugees into exile around the world. Everywhere they went, the starving emigrants took any work they could find, no matter how backbreaking or dangerous. Huge numbers poured into the labor force on construction projects in the fast-growing United States – in particular the railroads.

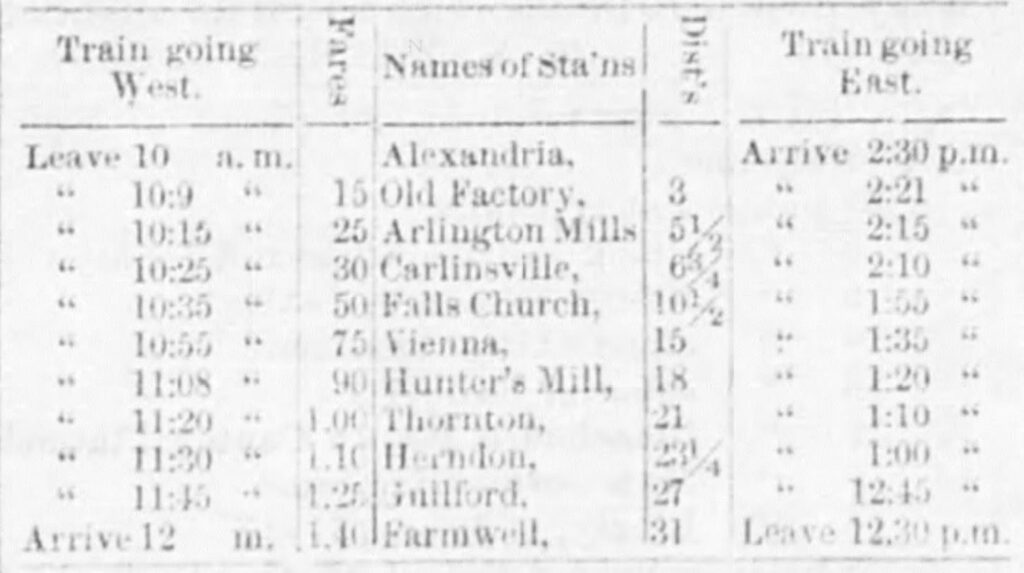

Thanks to the work of these particular Irishmen, by January 1860 the tracks of the AL&H – made of white oak ties and iron rails – had been laid all the way from Alexandria to Farmwell, and the first train ran to the new station building on what is now Ashburn Road. From there, a stagecoach carried passengers and mail west – it would be months before the tracks were completed to Leesburg.

Still, for the country people living around the Farmwell station, the prospect must have been intoxicating. In just two hours – and for just $1.40 – the iron ribbon of the AL&H could connect them with faraway Alexandria, and through that port, the rest of the world.

Living in the 21st century, with the wide world just beyond the departure gates at Dulles International Airport and massive construction projects regularly changing the landscape around us, it can be easy to overlook the significance of the railroad that came to Ashburn in the 1850s.

For the most fitting memorial to the project, one need only take a walk on the W&OD Trail, and look around. As McCray puts it, “The fact that most of the structures and features of the railroad still exist 170 years later is a testament to the skills of those who built the railroad.”

(Top image: While no photos were located showing the railroad through Ashburn under construction, phtoos of similar work elsewhere illustrate the era. At the top of this story, we see a rare photo showing railroad construction under on another line in Virginia.)

Mathew Annis is a freelance writer who lives in Ashburn. He previously wrote the article “Death at the Toll House” in our September 2020 issue.