ON THE FRONT LINE OF CHANGE

By Chris Wadsworth

The year was 1966. Dr. Robert L. Green was in the front passenger seat of a car driving through Belzoni, Miss. With him was Andrew Young, the future mayor of Atlanta and a future congressman. In the backseat was the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the famed civil rights leader.

“We were in the car… and James Belk, the owner of the Texaco station, was pumping gas,” Green recalled. “We stopped at the light. Belk looked up. He saw King. He stopped pumping the gas. He ran up to the car and he pulled his pistol out and he put it up to King’s forehead and he said, ‘Martin Luther King, I’m going to blow your brains out.’ And King turned to him and said, ‘Brother, I love you.’ The guy was stunned. That pistol came down and he put it in his pocket, and he went back to pumping gas.

“Andy Young said, ‘Martin, why do you do that? One day you’re going to get us all killed.’ And King said, ‘J.F.K. had all sorts of protection. When they are ready for me, they are going to get me.’”

These are the kinds of memories that swirl in Green’s head. He had a front row seat to some of the most intense and pivotal moments during the Civil Rights Movement as a prominent leader during that tumultuous era and the decades that followed.

Today, he is a 90-year-old retiree living quietly in Ashburn’s Brambleton neighborhood with his wife of 67 years, Lettie, and two of his three adult sons.

CHILDHOOD LESSONS

Green was born in Detroit in 1933 and grew up there, graduating from Northern High School in 1952, where he ran track and played football.

He says his neighborhood was a mixture of Blacks, Italians and Jews who all lived together without too many problems. Despite the relative harmony, like every Black child he eventually learned about racism.

“I worked in an Italian barbershop when I was 9 or 10 years old,” Green said. “I would hear the n-word and didn’t quite pick up on it at first. But after a while I did.”

Green’s parents, including his dad, who grew up in the segregated Deep South, gently taught their son to always be cautious.

“My mother said, ‘Be careful.’ If I went downtown to pay a bill, be careful. And especially don’t speak to white men,” Green said. “She had her way of letting you know that you could get in trouble with certain members of certain races.”

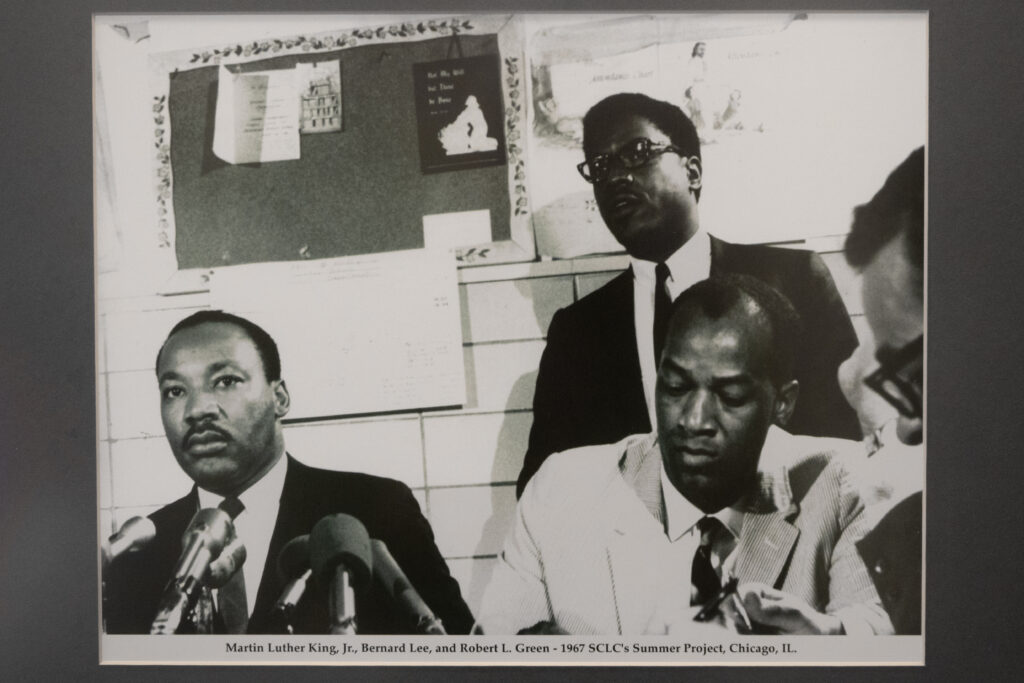

In 1954, Green was drafted into the U.S. Army and stationed in San Francisco for his two years of service. He earned his bachelor’s degree in psychology and then a master’s degree in school psychology at San Francisco State College. He then moved to East Lansing, Mich., and earned his Ph.D. in educational psychology at Michigan State University in 1963.

JOINING THE FIGHT

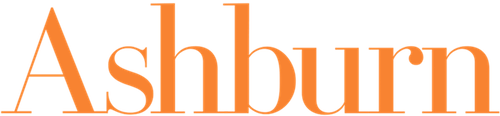

In 1965, Green took a leave of absence from teaching at Michigan State and joined the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, a civil rights organization led by King. The two men worked together closely and became friends.

“It was an experience,” Green recalled. “Dr. King – to me – was a brilliant person. A good man. Unafraid. He said, ‘If you’re afraid of dying, but you don’t have anything you’ll die for, maybe you ought not to be living.’ When King said that, it really blew my mind.”

And the feelings were reciprocated. In February 1966, King wrote a letter to Michigan State thanking the school for sharing Green with the SCLC.

“Through his brilliant mind, his broad humanitarian concern and his unswerving devotion to the principles of freedom and human dignity, he has been an inimitable influence for good on our staff,” King wrote about Green.

King asked Green to be the organization’s education director. This took Green into the segregated South – where he finally started to understand the world in which his father had grown up.

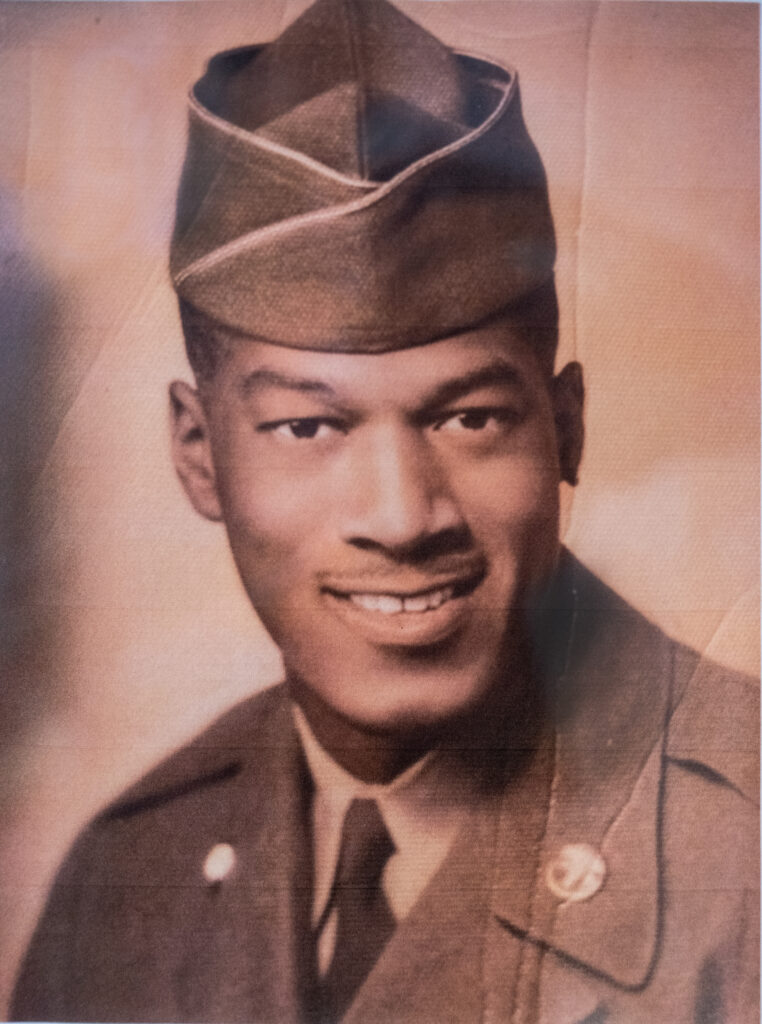

In Grenada, Miss., a sheriff was intimidating Blacks, Green said. “Blacks in the backwoods had whispered to me that he had even killed some Black men. I asked what did they do – and they said sometimes they didn’t do anything. I began to understand the fear that Blacks had in the South and the price they paid for living there.”

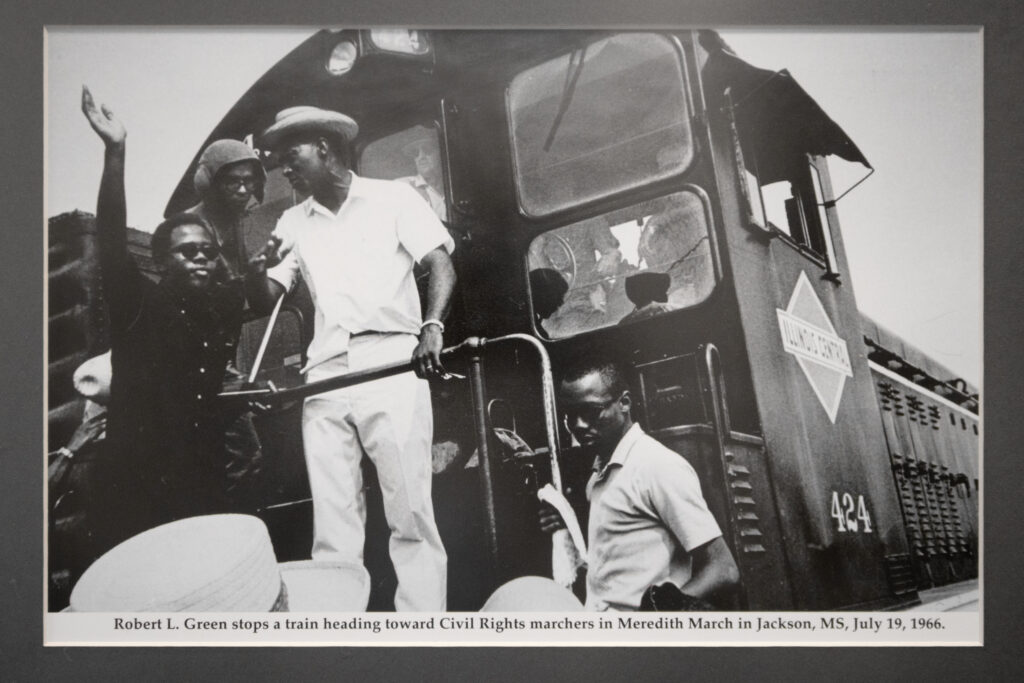

MEREDITH MARCH

One person who paid a price was James Meredith, a civil rights activist who became the first Black student to enroll at the University of Mississippi in 1962. In June 1966, Meredith began marching across Mississippi to protest efforts to keep Blacks from registering to vote. On the second day of his trek, a white man shot him multiple times, putting Meredith in the hospital.

SCLC leaders, as well as those from other organizations, descended on the state. King asked Green to lead the quickly growing crowd in what became known as the Meredith March.

At one point during the journey from Memphis, Tenn. to Jackson, Miss., the marchers blocked a train track and an oncoming train. The engineer slowed to about 5 mph – but was still inching toward the protesters – many of them white students from the North.

“I said, ‘Oh my God, if he hits one of those students – white or Black – all hell is going to break loose,’” Green remembered. “I climbed up and I talked to the conductor, and I could tell he was afraid. I said, ‘Sir, I’m going to be honest with you. If this train touches one of these 20,000 people, these northern students are going to tear you limb from limb and I’m not going to be able to stop them.’ He stopped the train.”

MLK ASSASSINATION

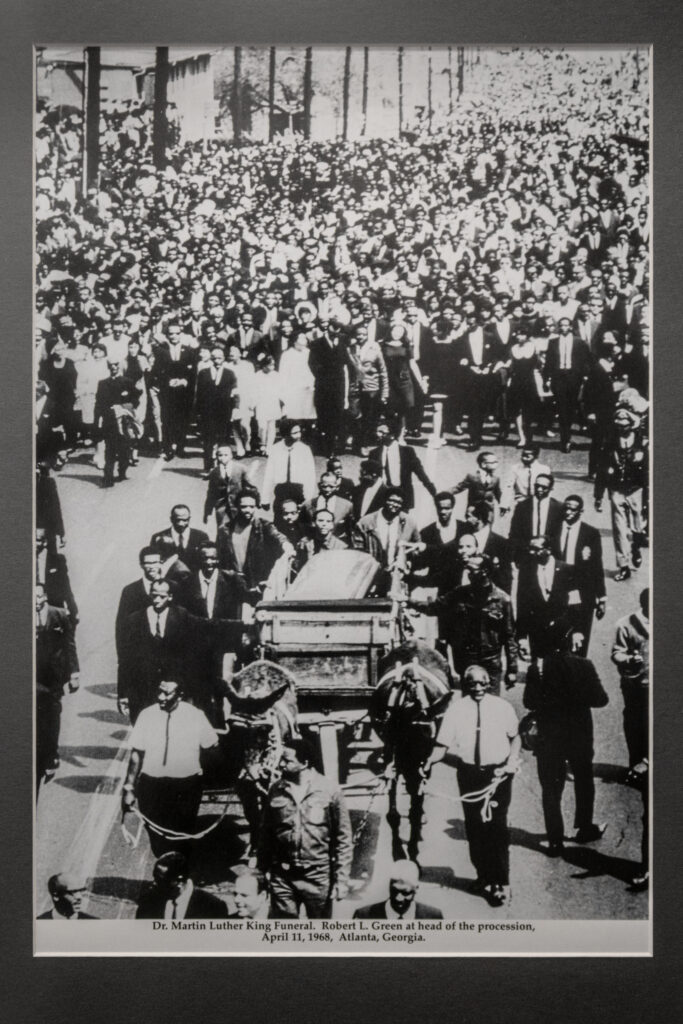

By 1968, Green had resigned from the SCLC and returned to East Lansing and Michigan State. On April 4, he and his wife were at home getting dressed to have dinner with another couple when Green got a call from Andrew Young’s wife, Jean.

“She said, ‘Martin’s been shot.’ I said, ‘Is he still alive?’ She said, ‘I don’t know. I’m going over to Mrs. King’s house now.’ She called me back about 15 to 20 minutes later and said King was dead,” Green remembered.

He was devastated by the loss of his friend and mentor – but there was no time for grief. Angry students were already flooding the Michigan State campus.

“I remember one said, ‘We’re going to burn the university down,’ and I said, ‘You can’t burn it down because it’s made of brick,’” Green said.

Instead, he worked with local police to defuse the situation, reserving a ballroom at the campus union for a mass meeting where students could express themselves. “I felt my job was to keep things peaceful on the campus so we could continue to work there.”

Days later, he marched alongside King’s casket through the streets of Atlanta.

Dr. Theodore Ransaw is a research specialist at Michigan State and has worked closely on several projects with Green. He finds Green and other leaders of that era inspiring.

“These men were completely fearless. They led by faith,” Ransaw said. “I often think of Dr. Green and his faith. He had his faith in the Civil Rights Movement. He had his faith in Dr. King. And he also had a lot of faith in his students.”

DESEGREGATING EAST LANSING

In Michigan, Green and his young family eventually wanted to buy a house. But the leading real estate agents refused to work with him or sell him a house. They wanted to keep Black residents out of East Lansing.

Green reached out to George Romney (father of Sen. Mitt Romney), Michigan’s governor at the time.

“I said, ‘Mr. Romney, I can’t buy a home. I just finished my Ph.D., and no Realtor will sell me a home,’” Green said.

Romney put him in touch with other leaders, and Green filed a complaint with the Michigan Civil Rights Commission. The commission investigated and then ordered a local realty company to sell a house to Green. But Green didn’t want the company and its racist real estate agent to profit from him, so the family bought a different home.

It was a frightening time, but Green says he never really felt fear during the housing fight.

“I always felt blessed that no one ever attempted to hurt my family,” Green said. “Because I’m not so sure I would have abided by Dr. King’s non-violence [stance].”

The Greens’ home was at 207 Bessemaur Drive – and still stands today. A historical marker was placed in the park next to the home in 2021 commemorating Green’s fight to desegregate East Lansing.

Nearby, the former Pinecrest Elementary School – a school Green’s sons helped desegregate when they were some of the first Black students to attend – has been renamed the Robert L. Green Elementary School.

“It’s just mind-boggling,” said Green’s son, Kurt Green. “It’s an incredible tribute to the work that my dad did in that community.”

A LIFE WELL LIVED

Green went on to lead Michigan State University’s Center for Urban Affairs and then became the school’s dean of the College of Urban Development, a post he held until 1982. From 1983 to 1985, he was the president of the University of the District of Columbia.

Today, sitting in his office at his Ashburn home – its walls covered in historic and dramatic black-and-white photos from the Civil Rights Movement – Green is proud of the role he played in this critical time in American history.

“I did all I could. I was not fearful of danger. I protected people when I could, and I did not judge people in a negative way,” he said.

“There were some Blacks that were pretty angry with the way they grew up and the way they were treated by whites. But I always told my sons – all whites aren’t the same, just like all Blacks aren’t the same. I think that, more than anything else, was something I got from Martin Luther King Jr. Don’t judge people based on the experience you’ve had with someone who looks like them. You can sometimes be so very, very wrong.”

– Brambleton resident Larry Lichtenauer contributed to this article.