CLICKING THROUGH HISTORY

By Chris Wadsworth

Imagine wanting to explore your ancestry and family history, only to hit a brick wall. Literally all family references and links disappear.

This is the situation many African Americans find themselves in – for an obvious reason. Before 1865, some, even many, of their ancestors were enslaved and considered “property.” There was no reason to keep certain life records – births, baptisms, marriages, deaths – on “property.”

But Morven Park – the grand estate in Leesburg that, ironically, was once home to enslaved individuals as well – is working to help Blacks trying to build their family trees. And they’re doing it with the assistance of a team of students from Stone Bridge High School in Ashburn.

It’s called the “246 Years Project” – which aims to document and honor the millions of enslaved men, women and children whose names and stories deserve to be known.

“It’s good news, bad news,” said Stacey Metcalfe, executive director and CEO of Morven Park. “The bad news is they were considered property, but the good news is that houses like this have records. There are a lot of documents that contain a lot of information about the people – including the enslaved people – that lived and worked here and across our county.”

The 246 Years Project is taking those records – more than a century old – and entering them into an online, searchable database that is free and available to all.

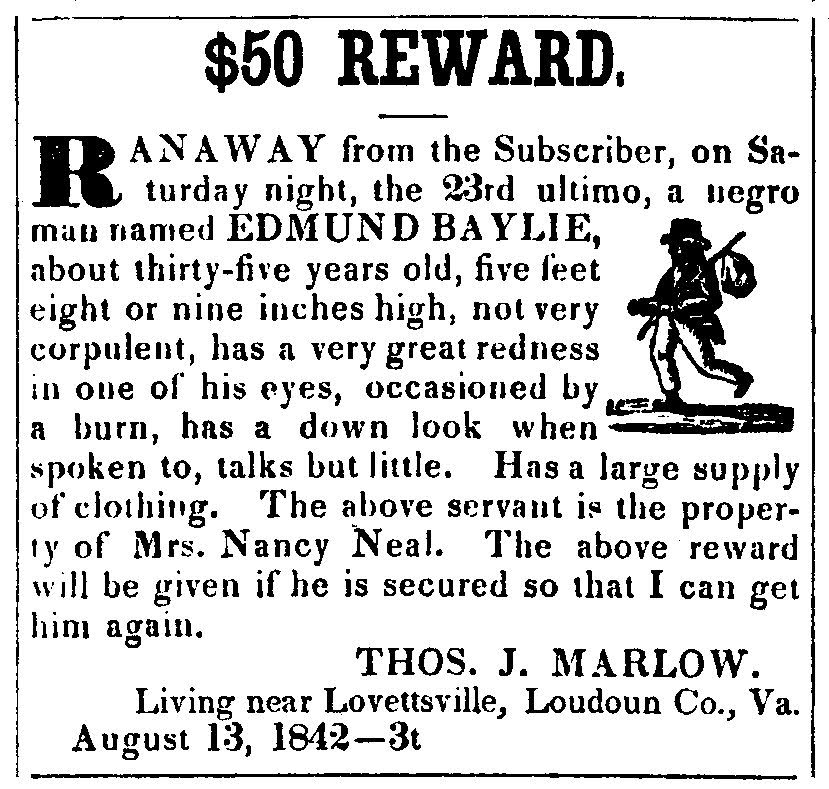

The records include all kinds of things – court records, bills of sale, newspaper advertisements and more.

Jana Shafagoj, director of preservation and history at Morven Park, who developed the idea for the project, said the team started data entry with the records from the Loudoun County Clerk of the Circuit Court Historic Records & Deeds Office. “They hold the largest single collection of records with information of enslaved people in Loudoun.”

By late December, the database held nearly 3,000 documents with the names of more than 13,000 enslaved and emancipated people. About 40% of the documents are publicly available, and the rest are going through a review process before going live online.

Another source of information – painful as it is to consider – are the flyers that used to be distributed when an enslaved person “ran away.”

“Not only do these documents often describe the names of people, but the genealogical connections,” Shafagoj said. “Whole family units would flee together so it provides physical descriptions, height, appearance, things about their speech patterns, scars, things that would help identify a person as well as where they had family and where they might be headed for.”

All this information goes into the database. Each word and fact is a possible thread to connect to another thread until a history can be woven.

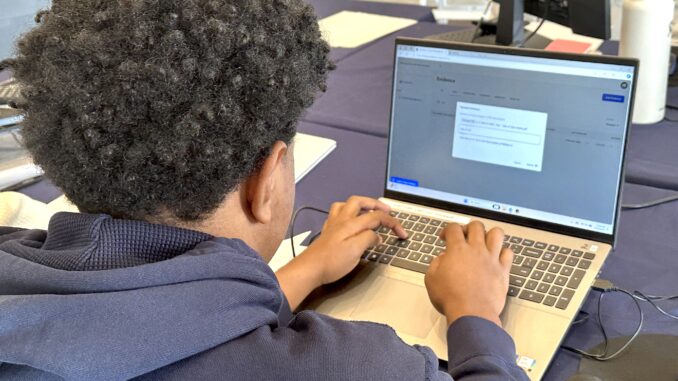

And that’s where the kids from Stone Bridge come in. They are helping enter everything into the database – a sometimes painful experience.

“I was shocked,” said senior Amari Kamara. “Human beings – just like everyone else and they are being sold.”

Sophomore Julie Belk said she didn’t realize how prevalent slavery was in Loudoun. “It’s very much rooted here in Ashburn and Loudoun County. It’s very sad their stories are not yet told.”

The 246 Years Project has been in the works for years, but it formally launched last May, when the database went live. While right now it is focusing on Loudoun and Northern Virginia, the hope is to take it nationwide – linking records from hundreds of historic homes and thousands of courthouses, newspapers and other sources.

“What’s going to be magical about these databases is when you start making the connections,” Metcalfe said. “Someone was sold down to Georgia, and you start following that trail and it will expand outside of Loudoun and outside of Virginia.”

The 2024-25 cohort of student volunteers is the second from Stone Bridge. Senior Mejd Hutchinson, part of this year’s cohort, has spent time exploring his own family history.

“It was a lot of work,” he said. “My whole family was Palestinian, and we can find our family history like 600 years back.”

He learned both of his grandfathers were doctors and one of his great uncles was a lawyer. He looked through old family photos and found images of distant cousins. Now, he wants to give others that same opportunity by working with the 246 Years Project.

“I’m trying to help people find their heritage, find their ancestors,” he said. “The more you talk about their [ancestors’] stories, the more it keeps them alive.”

Carla Davis, a social sciences teacher at Stone Bridge, oversees the volunteer students under the auspices of an African American history class. She’s thrilled with what the experience has given her students – but it’s also a little bittersweet.

“The only thing I feel a little sad about is that we don’t incorporate this part of our American history, our American story, into other classrooms,” Davis said. “Why do we have to have separate classes for separate histories? But I am grateful even if it’s in this segregated class to have the opportunity to teach them things they missed in their regular U.S. history class.”

Although the current students’ time on the project is almost over, the work will go on. Several dozen other citizen volunteers are also regularly entering information into the system.

Next up, historic documents from the Balch Library in Leesburg as well as material from Oatlands, another historic home in Loudoun.

“We do not anticipate an end to the 246 Years Project,” Shafagoj said. “There is no limit to the individual lived experiences and stories that will emerge. … Pulled together, these stories will expand our understanding of American history.”

To learn more about Morven Park’s 246 Years Project or explore the database – visit morvenpark.org/246years