Trailing an Assassin

By Glenda C. Booth

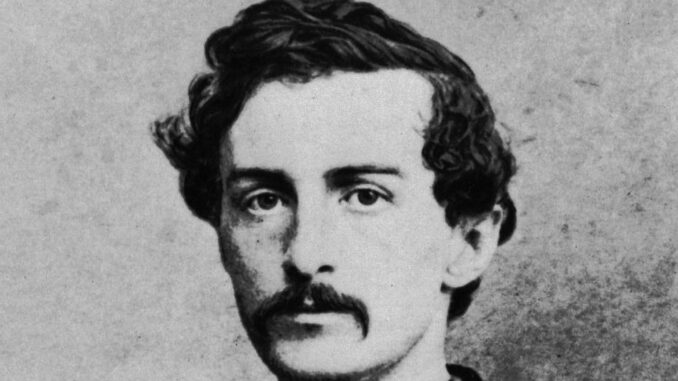

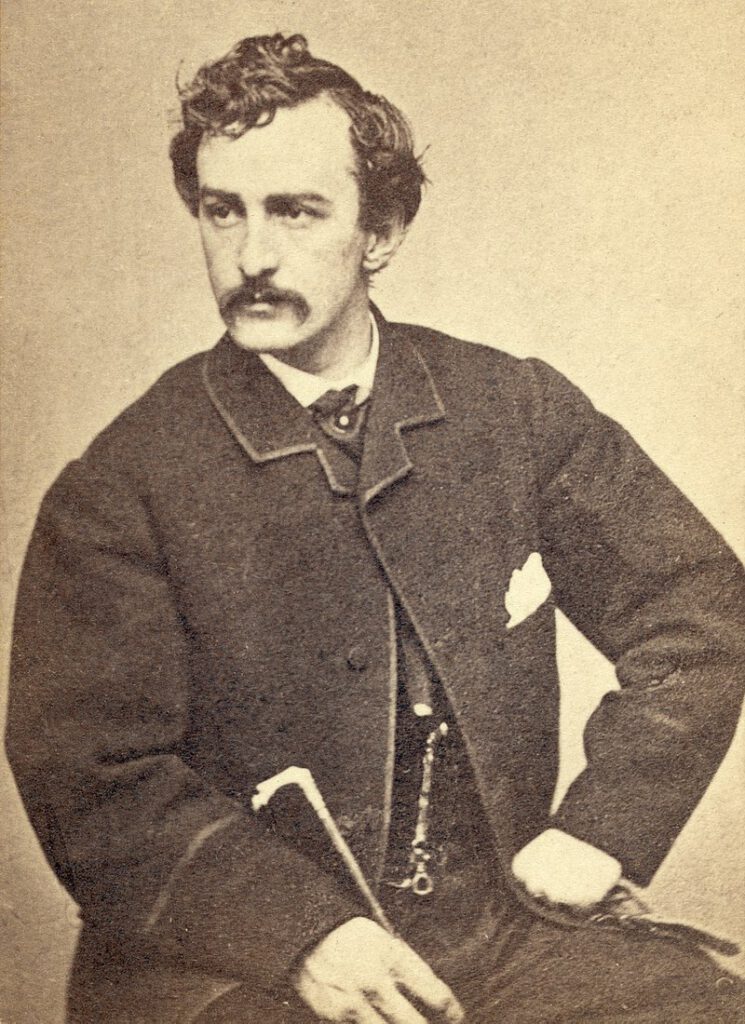

John Wilkes Booth assassinated President Abraham Lincoln at Ford’s Theater in Washington on April 14, 1865, at 10:15 p.m. A Confederate sympathizer and actor, after shooting Lincoln, he leaped from the second-floor balcony onto the stage, charged out the back door and galloped into Maryland in the dark of night with his accomplice, David Herold.

Booth’s motivation, plot and attempted escape through Maryland and Virginia have intrigued professional and amateur historians for 157 years. Retracing his route today still provokes questions: Who helped them along the way? Was the route planned? What was their ultimate destination?

Once today’s travelers escape the Washington suburbs and drive into the quiet countryside of farm fields and dense forests, it’s easy to envision two desperate men on horseback charging at a fast gallop down rural dirt roads in the dead of night, sneaking in and out of farmhouses and hiding in swamps and thickets.

History buffs can retrace Booth’s and Herold’s 12-day, 66-mile journey from Ford’s Theater to Port Royal, Virginia, a small town on the Rappahannock River east of Fredericksburg. There, Booth met his demise and Herold surrendered.

Ford’s Theater (1)

511 10th St. NW, Washington

Lincoln and his wife, Mary, were watching “Our American Cousin” from the balcony’s presidential box, along with 1,400 other people sitting on portable wooden chairs. During a laugh line, Booth shot the president in the back of the head with a derringer handgun.

Ever theatrical, Booth then jumped 12 feet from the balcony onto the stage and accidentally snagged his boot spur on either the framed photograph of George Washington or a flag draped across the balcony. When he landed, he broke his left fibula. Chaos ensued, and Booth disappeared into the night.

The theater today looks much as it did in 1865. The museum under the theater explores Civil War Washington up to the night of Lincoln’s death and houses over 3,000 items related to the assassination, including Booth’s gun, dagger, diary and compass, and features life-size replicas of four conspirators.

A major piece of incriminating evidence on display is Booth’s boot that Dr. Samuel Mudd removed later that night to stabilize the fugitive’s broken bone. Mudd stashed the boot under the bed Booth used. Because it had Booth’s name inside, authorities surmised that he had been at the Mudd farm.

The Surratt House Museum (2)

9118 Brandywine Road, Clinton, Md.

Maryland did not secede from the union, but in the 1860s, it was heavily pro-Confederate and slavery was legal. Southern Maryland was the pair’s immediate destination.

From Ford’s Theater, Booth and Herold raced across the city to the Navy Yard drawbridge. Booth’s horse was lathered in sweat, the bridge tender observed. They made their first stop 13 miles south of Washington at Surratt’s Tavern, owned by John Surratt Jr., in what is now Clinton, Md. The tavern was a Confederate safe house for spies and couriers, and the conspirators had hidden supplies there.

In the seven minutes they were there, Booth did not go in. Herold went in and got rifles, field glasses and whiskey. Because of his injury, Booth could not carry a carbine as planned, so John Lloyd, a former police officer who ran the tavern, crammed the gun inside an upstairs wall.

Today, visitors can explore eight rooms restored to the 1860s appearance of what was then an “ordinary,” a combined tavern-hotel at a strategic crossroads. On a self-guided tour, people can learn about tavern life, Maryland’s enslaved people, the Reconstruction era and view the shaft where Lloyd hid the carbine Booth and Herold left behind.

The Mudd House (3)

3725 Dr. Samuel Mudd Road, Waldorf, Md.

Booth was in pain and decided to seek help from his acquaintance, Dr. Samuel Mudd at Mudd’s Bryantown farm. They arrived around 4 a.m., with Booth claiming to have fallen off his horse. Mudd cut off Booth’s boot, set the leg and allowed the two fugitives to rest in a second-floor bedroom, while a thousand or so men scoured the countryside, searching for the assassin.

Today, docents lead tours of the seven-room Mudd farmhouse, built in 1830 and presented as it appeared in 1860, when it was a 218-acre tobacco, corn and wheat farm called St. Catherine. About 90% of the furnishings are original from the time Mudd and his wife lived there.

On the second floor – in what’s now called “The Booth Room” – is the actual bed where Booth slept. Mudd’s first-floor country doctor’s office has his original mortar and pestle used for grinding and mixing medicines. In the little-changed kitchen are the original toaster, juicer and potato ricer of that time. For Mrs. Mudd, as well as a servant and four children, the home was a “prison” for a week as Union soldiers held her under house arrest.

Eventually, Mudd was convicted of aiding and abetting Booth and imprisoned for four years at Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas islands. At the farmhouse are two shelled jewelry boxes, a cane and a table that he made at the prison. After President Andrew Johnson pardoned Mudd in 1869, he returned home and had five more children. He died in 1883 and is buried at St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Bryantown, where his tombstone still stands.

After Mudd’s Farm

On the morning of April 15, when Dr. Mudd learned that federal troops were swarming the area, he sent Booth and Herold on their way. The pair camped in boggy Zekiah Swamp, where Thomas Jones, a Confederate sympathizer, brought food and newspapers and coordinated plans to transport them across the Potomac River to Virginia.

One journalist of the day wrote about the swamp, “No human being inhabits the malarious extent.” At 21 miles long and half a mile wide, today it’s the Zekiah Swamp Natural Environment Area (4) near Brandywine.

After five long, cold days in the swamp, Booth and Herold went to Rich Hill (5), the home of Samuel Cox near Bel Alton, about 18 miles south of the Mudd farm. Cox gave them a meal but, fearful of being associated with them, told them to hide in a nearby pine thicket. The house today is a private residence that can be seen only from the roadside. Today’s pine thicket is likely a remnant of the hideout site.

On the night of April 21, Jones led the two fugitives to the Potomac River, where he had hidden a rowboat. The river was two miles wide at this point and patrolled by Union officers in gunboats. Today’s visitors can view the crossing point from bluffs above the river.

In Virginia, they made their way to Elizabeth Quesenberry’s home (6). A Confederate underground operative, Quesenberry gave them food and fresh horses. They ventured onward another 16 miles or so south and crossed the Rappahannock River on a ferry at Port Royal. Union detectives learned that the two had made it to Virginia.

Booth and Herold then sought refuge at Richard Henry Garrett’s farm (7) near Port Royal. Garrett made them sleep in the tobacco barn and, worried that the two men would steal his horses, he locked the barn.

On April 26, the federal cavalry surrounded the barn and set it afire. Herold surrendered, but Booth, heavily armed, resisted arrest. At some point after 2 a.m., Army Sgt. Boston Corbett shot Booth in the neck. Booth died later that morning at age 26. Soldiers found his planning documents, compass, diary and photos of five women among his possessions.

Today a roadside Virginia historical marker titled “Where Booth Died” is on U.S. Route 301 just south of its intersection with U.S. Route 17, near the former farm.

Booth and Herold were on the run for 12 days, aided by Confederate agents and accomplices, historians contend. The assassination and their attempted escape had generated the most massive manhunt in history.

Glenda Booth is a freelance writer based in Virginia — no known relation to John Wilkes Booth. She writes for publications around the state.