WHO WAS BAZIL NEWMAN?

By Jill Devine

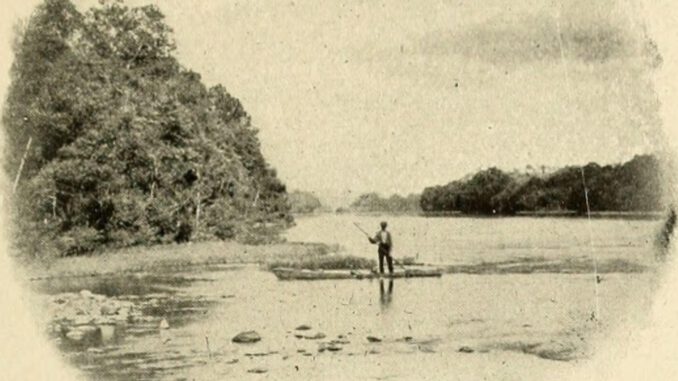

Loudoun County has seen many changes throughout history, but one thing has remained constant: the unyielding beauty of the Potomac River that defines its northern border. The sun that shines on its sparkling waters today is the same sun that shone on 19th-century Loudoun boatsman Bazil Newman.

Newman was a free Black ferry operator who, despite significant obstacles and discrimination in pre-Civil War Virginia, became a successful entrepreneur, businessman and owner of at least 186 acres of farmland where Goose Creek joins the Potomac.

Today, most of Newman’s former property is in the affluent golfing community known as River Creek. And the site of his former business property across the water — long a Loudoun County park — has been renamed in his honor. More on that in a moment.

A FREE BLACK MAN IN A SLAVE STATE

Born to a white mother and a Black father in November 1779, Newman was not positioned for an easy life in Loudoun. He was a free Black man during a time when slavery thrived. A 1790 census recorded that Loudoun’s population of 18,962 included 4,213 who were enslaved.

Loudoun differed from most of Northern Virginia and the antebellum South in that, in addition to plantation owners who held enslaved workers, it was home to many Quakers, Germans and Scottish Irish who had migrated from the North with anti-slavery views. Several free Blacks lived in Loudoun, but they were required to carry a “freedom” paper that verified their legal status everywhere they went.

Life was hard for people like Newman. Because free Blacks posed a perceived threat to a slavery-dependent society, white leaders passed laws to control their progress. In 1806, the Virginia General Assembly decreed that African Americans emancipated after May 1806 had 12 months to leave Virginia or face re-enslavement. In 1831, the Virginia General Assembly passed laws forbidding African Americans in Virginia to assemble, learn to read or write, or preach.

“The most interesting thing was the fact that he was so respected and trusted for an African American man living at that time,” said Lori Hinterleiter, a member of the Black History Committee with the Friends of the Thomas Balch Library in Leesburg. “Land ownership for free Blacks existed then, but that he owned so much land, had a business and operated a ferry was pretty remarkable.”

A LIFE BUILT ON THE POTOMAC

In a 2019 report of the Loudoun County Heritage Commission, author Bronwen Souders wrote that by 1820, Newman was living with a free white woman (interracial marriage was illegal), presumably the mother of three children — two boys and a girl. Eventually Newman had three sons: Basil, Benjamin and Robert. By 1836, he was living with a different white woman named Cornelia, with whom he appears to have had a daughter named Sophy. Many family members, including Bazil’s younger brother, Hezekiah, joined the family tradition of working on the Potomac as boatmen.

Free Black boatmen at the time were under constant suspicion of aiding runaway enslaved persons, who would cross the Potomac and travel through Maryland to freedom in Pennsylvania. The Virginia General Assembly required that Black boatmen obtain certificates from “respectable white persons” to verify that their shipping manifests were accurate.

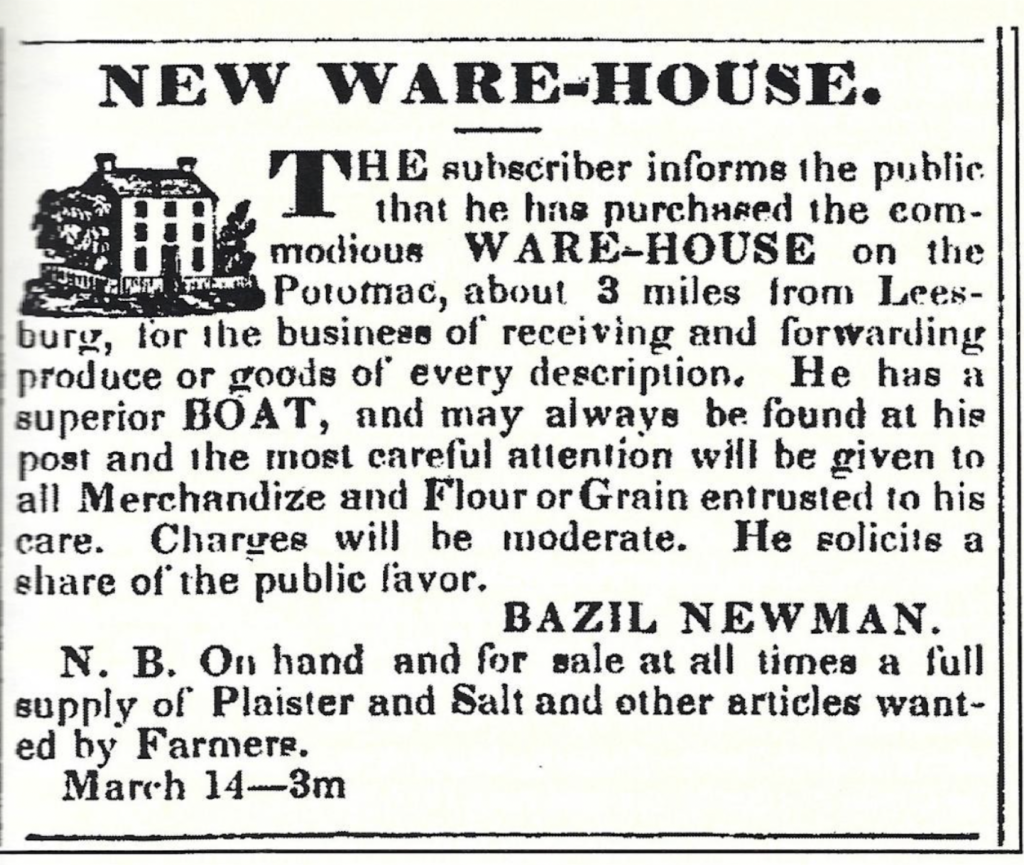

In 1839, a white man named William Shreve built a warehouse on or near Newman’s land at Goose Creek. He put several ads in Leesburg’s weekly “Genius of Liberty” publication advertising that he had bought a “commodious WARE-HOUSE on the Potomac, about 3 miles from Leesburg, for the business of receiving and forwarding produce or goods of every description.” Shreve touted the ferry services of Bazil Newman as a “well-known and experienced boatsman.”

By spring 1840, Newman himself was placing ads notifying the community that he had bought the warehouse, adding that he had a “superior BOAT,” and that he “may always be found at his post and the most careful attention will be given to all Merchandize and Flour or Grain entrusted to his care.”

FERRYING OTHERS TO FREEDOM

As a man who spent his life poling boats along these waters, Newman probably knew the river better than anyone in Loudoun. Evidence suggests that he or family members used that knowledge to escort the enslaved across the river as part of the Underground Railroad.

Several escaped enslaved people attested to traversing the river at or near where Newman plied the Potomac. One example — a preserved diary entry written by white Loudoun resident Mason Ellzey references such a boatman: “It afterwards came to be known that the ferryman at Edwards Ferry, on the Potomac, was the underground agent of these organized thieves, at the ferry, and the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal was a part of the route which received, on certain boats, fugitives brough over the river by the ferryman.”

Across the creek from Newman’s property, on land that is present-day Lansdowne, Newman operated his warehouse and was part-owner of a gristmill that had been named Elizabeth Mills years earlier after Elizabeth Clapham, the wife of a local slaveholder.

Loudoun leaders eventually designated the area surrounding the historic relics of the mill as a recreational facility, naming it Elizabeth Mills Riverfront Park, with an upstream canoe launch named after George Kephart, a prominent resident and slave trader who used Goose Creek to transport the enslaved between ports.

TURNING THE PAGE

The Loudoun Board of Supervisors turned a fresh page in history on Feb. 15, 2022, when it voted to rename the area as the Bazil Newman Riverfront Park in honor of Newman’s accomplishments as a free Black man and probable collaborator in the Underground Railroad. The canoe launch was renamed Riverpoint Drive Trailhead. New signage has been installed.

“For so many across the county, including myself, this has been a great learning opportunity,” said Koran Saines, Loudoun supervisor for the Sterling District. “I grew up here and can say with certainty that none of the information that was discovered as part of the renaming process was taught in our school system.”

Before Newman died in 1852, he signed a will leaving a 67-acre farm to Cornelia E. Harris, “who has lived with me for the last sixteen years in quality of a wife and who has been a faithful bosom companion and obedient housekeeper.”

The remaining acres were sold, with the proceeds divided among his sons. His gravesite still rests on a hillside on the west side of Goose Creek, surrounded by stately homes and manicured lawns at the 13th hole of the River Creek Golf Course.

Jill Devine is a freelance writer and former magazine editor from Loudoun County who writes for a variety of Virginia publications.