LUCK-Y BIRDS

By Glenda C. Booth

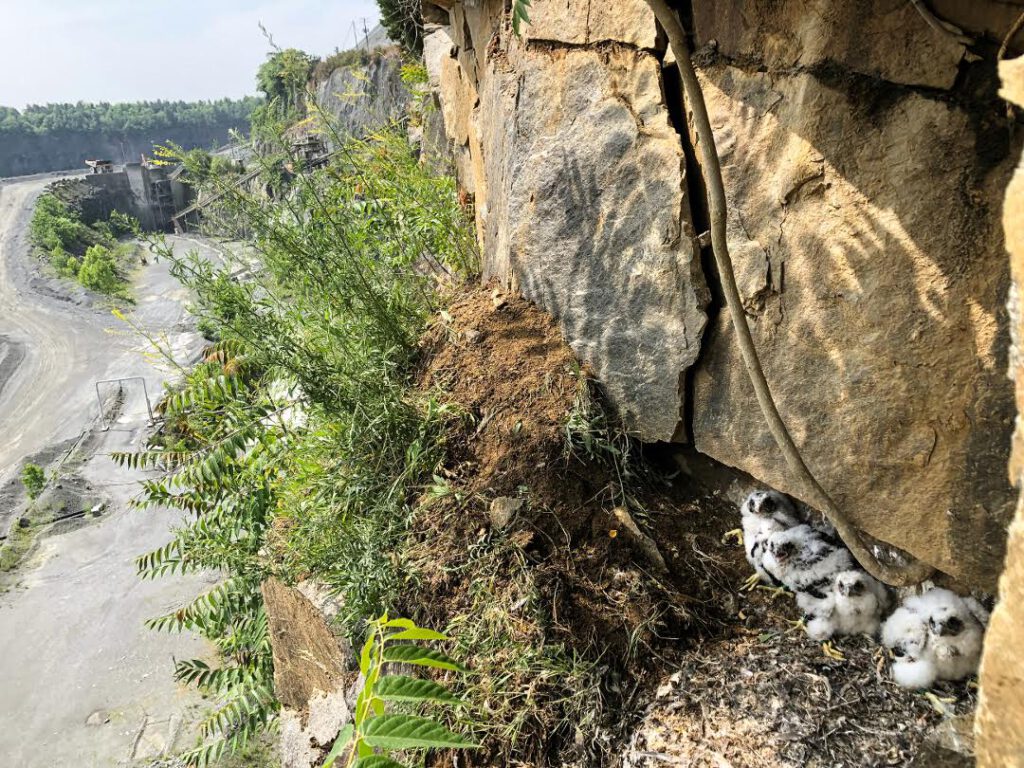

A narrow ledge 75 feet above the ground in a traprock quarry may sound like an inhospitable place to have and raise babies, but if you’re a peregrine falcon, it’s perfect. Last year, for the first time, a pair of falcons chose a ledge in the Luck Stone quarry just off Belmont Ridge Road in Ashburn for their home. There, the female laid four eggs, and the pair successfully raised three males and one female.

“They took my breath away” when he spotted them, said John Thompson, Luck’s regional operations manager.

Peregrines typically nest on cliffs, ledges, skyscrapers, water towers, bridges and other tall structures, so the sides of a quarry are perfect habitats.

“Quarries mimic natural cliff faces,” said Bryan D. Watts, director of the College of William & Mary’s Center for Conservation Biology.

DOWN THE QUARRY WALL

In May 2019, Watts climbed down the quarry’s wall to see the nest up close and to band the chicks for further study. He and an associate, ecologist Alan Williams, used climbers’ gear and rappelled down the sheer rock walls to the nest — also known as an “aerie.”

The scientists put each chick in a pet carrier and hung it on a sling attached to the wall. They banded the birds and took measurements. Then they returned the birds to the nest and climbed back to the top of the quarry. Job done. Further monitoring of the fledglings at Luck Stone was done from a distance with a long-range camera over several visits.

Scientists band birds in hopes there will be re-sightings. This allows them to study the birds’ migration, demographics and other factors. Watts partners with the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources, the National Park Service and other organizations and private companies to help track the banded birds. Having Luck Stone as a partner is a boon to their studies.

The quarry’s depth ranges from 50 feet to approximately 250 feet, and Luck mines diabase, a fine-grained rock used in concrete and asphalt. The nest was on a perimeter wall — in an area that will not be mined in the foreseeable future, according to quarry managers.

“They will likely play a significant role in future conservation efforts in Virginia and throughout the southern Appalachians,” Watts said. “We are very fortunate to have Luck Stone as a conservation partner for peregrine recovery.”

COMEBACK STORY

Peregrine populations declined worldwide in the mid-1900s, which experts attribute to the pesticide DDT. By the early 1960s, peregrines were believed to be done as a breeding species in Virginia due to the population drops.

“Egg-shell thinning, egg breakage, and hatching failure have all been attributed to elevated contaminant levels in females,” Watts said.

The tide started to turn in 1970, when the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service listed the birds as endangered and, in 1972, the Environmental Protection Agency restricted the use of DDTs.

In 1978, scientists started restoration efforts in the Virginia’s coastal plain and eventually in the mountain regions. Between 1975 and 1993, they released over 430 captive-reared falcons in the Mid-Atlantic and populations have risen steadily since.

Over the last three decades, 95 percent of breeding activity in Virginia has occurred in the coastal plain region along the state’s eastern shoreline. Watts’ team counted 30 breeding pairs statewide in 2019, which included two in Northern Virginia — the pair at Luck Stone and a pair in Reston. This was the third highest population recorded. The 61 young produced in 2019 was the most productive in Virginia’s history. This year, the team once again confirmed 30 breeding pairs nesting in the state.

“The population size is now around the estimated population size in the pre-DDT era,” Watts said.

Since the DDT ban, Virginia’s coastal populations have recovered more quickly than in other areas. While the falcons were removed from the federal endangered species list in 1999, Virginia still lists peregrines as “threatened” at the state level.

STATEWIDE EFFORT

Since 2000, National Park Service biologists have worked to bring peregrine falcons to Virginia’s mountains, once part of their historic range. Using a method called “hacking,” the park service team brings three- to four-week-old downy chicks from eastern Virginia bridges to wooden hack boxes on high cliff ledges in the Shenandoah National Park. For 10 to 14 days, staffers feed the captive chicks raw quail twice daily through a 2-inch tall, 14-inch wide opening, like a mail slot. The team hopes the birds will imprint on the park’s cliffs and return as breeding adults in two to three years.

When the falcons are ready to fly, at around six weeks of age, managers, hidden from the birds, open the box’s door slowly with a rope. Generally, the young falcons stay in the local area for several weeks. By late July, they begin to take extended flights of over 200 miles. By late August, they leave the area.

From 2000 to 2020, the park released 165 peregrines from four hack sites. Out of the 165 released, 155 successfully fledged, or grew big enough and strong enough to fly. At least two previously hacked falcons later returned to the park as a pair and built nests.

MORE QUARRIES, MORE FALCONS

Documenting a breeding pair in Luck Stone’s quarry was especially significant, Watts said.

“It is great to have pairs beginning to colonize the quarries because Virginia has quite a few both active and inactive quarries. Hopefully, the adaptation to the quarries will lead to more pairs in the state that are stable and productive.”

In 2020, devoted peregrine watchers searched all spring for a nest and parenting peregrines. Then in June, avid Ashburn-area bird watchers Theo and Calin Andronescu, who live in the Belmont Greene neighborhood, spotted and photographed four young peregrines flying over the Luck Stone quarry.

Tellingly, peregrine falcons born in Virginia in the spring typically fledge in June. So joy erupted among the scientists, local bird watchers and the folks at Luck Stone.

“We did not know about the nesting at Luck Stone [this year] until after the birds had fledged,” Watts said.

Luck Stone officials have taken to calling the birds “their peregrines.”

“We were so thrilled to have this bird in our quarry,” Thompson said. And they hope to see them back again next year.

PEREGRINE FALCON 101

- Peregrine falcon males are crow size, or roughly the size of a pigeon. The females are bigger — more the size of ravens. They have intense, dark eyes, “a steely, barred look,” according to Cornell University’s “All about Birds” website. They have a dark brown cap or hood and distinctive, dark sideburns. Their plumage is blue-gray above with vertical bars on the breast. The chin and throat are white to tawny buff. The powerful bill has a yellow base that transitions to gray and black at the tip.

- For nesting, the female makes a shallow depression called a “scrape” by scratching loose soil, sand, gravel, or dead vegetation. There, females lay from two to five creamy-brownish eggs. Peregrines mate for life. They also establish territories and usually space their nests seven to 10 miles from the next nearest nest.

- Peregrine falcons are speedy raptors, going as fast as 200 mph. They catch smaller birds in the air with spectacular dives called “stoops.” They often wait on high perches before making an aerial assault and capture their prey with their sharp talons, favoring slower-moving birds like grackles, blue jays, shorebirds, and waterfowl. Adult peregrines eat the equivalent of two medium-sized birds a day.

- Peregrine falcons are found in rural and urban environments and on every continent except Antarctica. They have a long history with people who have used them for hunting or falconry, as early as 2000 B.C. in China and Mesopotamia. In World War II, both the U.S. and the German armies had a falcon corps to intercept the enemy’s homing pigeons. Their name comes from the Latin word “peregrinus,” which means “to wander.”

(Photos courtesy of Matt O’Lear, Bryan Watts and Alan Williams)