TUNNEL THROUGH TIME

By Glenda C. Booth

Photos by Jack Looney

“Until you go there, you just don’t get the tunnel.”

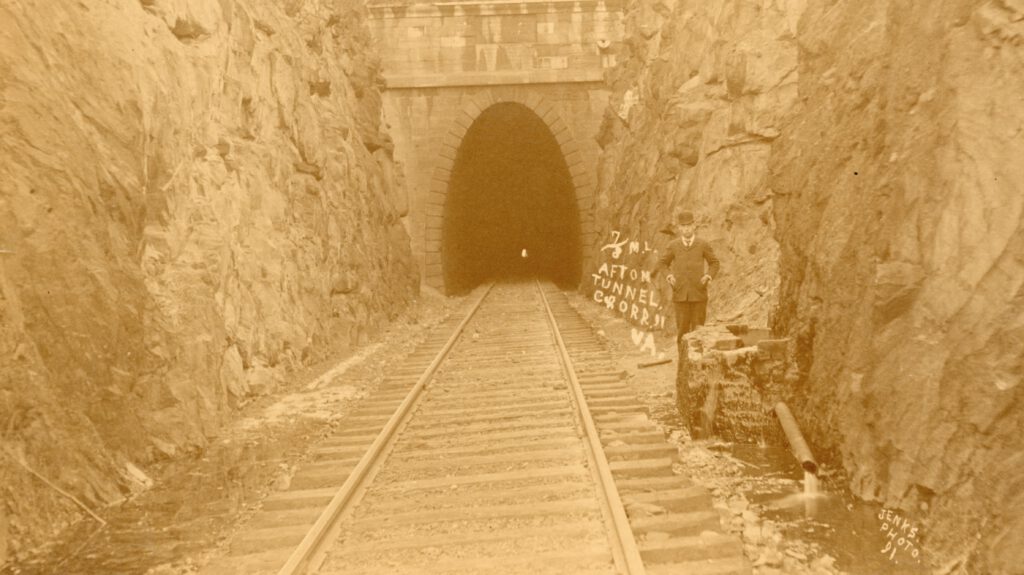

That’s what Paul Wagner says about the Blue Ridge Tunnel, a 4,273-foot underground passageway, dug mostly by hand in the mid-1800s. Wagner should know – he directed a documentary about this engineering marvel, located under Afton Mountain about 22 miles west of Charlottesville.

“There’s something symbolic, metaphoric,” he muses in his film. “There’s something powerful about the notion of a tunnel.”

Indeed, adventurers seem to love to amble through the historic railroad tunnel turned pedestrian footpath and tourist attraction. It opened to the public in November 2020, and by the end of 2021, more than 130,000 visitors had ventured into the nearly pitch-dark mountain passage.

There’s something magical, even mesmerizing about it. Visitors stroll in near darkness under an arch of hard, raw, greenstone rock. In the distance is a tiny, white orb of light, the tunnel’s other opening, which grows larger and larger as you approach it. It’s nearly impossible to determine how far away that dot of daylight is, but it’s a magnet, pulling walkers ever closer.

Walking through evokes awe and goosebumps, as well as admiration for the workers who put their lives at risk to blast the tunnel.

Early American leaders like President George Washington championed canals and rivers for commercial transportation between Virginia’s Tidewater and western regions, but by the mid-1850s, some argued that canals would be inadequate and impractical. Claudius Crozet, who had studied engineering in France and served in Napoleon’s army, had another idea – burrow through Afton Mountain.

Crozet came to the United States at age 26 in 1815, taught engineering at the U.S. Military Academy and then was chief engineer for the Virginia Board of Public Works. He was a founder of the Virginia Military Institute and president of its board. Thomas Jefferson called him “by far the smartest mathematician in America.”

At the heart of the tunnel’s history are the 800 Irish immigrant workers and around 300 enslaved men who built it between 1850 and 1858, working eight to 10 hours a day. The Irish workers came to America to escape the famine in Ireland. They lived with their families in nearby shanties and initially earned $1 a day.

Slave masters regularly rented out their enslaved workers in those days, but these owners insisted that their slaves not do any blasting, not because the owners were altruistic, said Wagner, but because they wanted to protect their financial livelihood.

“It’s just so revealing of the way slavery worked as an institution,” Wagner said. “It helps you see just how twisted it really was.”

The enslaved workers labored as blacksmiths or floorers who cleared the rock debris after the detonations.

Clues to the construction methods, such as grooves in the hard rock walls, are visible today. Workers hammered long star drills into the rock, filled the cavities with volatile black powder and fuses, and lighted the powder. The blasting filled the work area with debris. It was cold, nasty, dangerous work. Some workers suffered injuries like lost fingers. Some were lost to cave-ins and explosions. Forty died from cholera.

Usually, a 100-member crew labored on one side of the mountain and another 100 on the other side, inching along to meet in the middle. Each crew built 20 feet a month, a superhuman engineering feat that took around eight years.

Crozet devised ventilation and drainage systems and had to battle skeptics who questioned whether the two parts would actually align.

“When the crews finally ‘holed through’ on Christmas Day, 1856, not only did the tunnels meet exactly, but Crozet’s calculations were found to be so precise that only one-half-inch separated their alignment,” reads the National Historic Civil Engineering Landmarks website, where the tunnel is listed.

It was the longest railroad tunnel in the nation in its day. It is 16 feet wide to accommodate trains and has a 51-foot descent from west to east. At its deepest point, it is about 700 feet below the surface.

In 1858, the first train rumbled through. The tunnel provided rail access through the Blue Ridge Mountains, connecting the Piedmont with the Shenandoah region. Trains carried products like imported goods and oysters from Virginia’s eastern region to the west and farm products from the west to the east.

In 1944, the tunnel closed, and the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad replaced it with another tunnel 40 feet deeper. In the 1950s, the Dixie Bottled Gas Corp. built two, 12-foot-thick concrete bulkheads at either end in an attempt to store propane in the abandoned tunnel, but this did not succeed.

The tunnel was largely forgotten until 2001. Allen Hale, then a member of the board of supervisors of Nelson County, where Afton Mountain is located, convinced the board to explore the tunnel’s restoration and use it as a pedestrian trail. In 2007, the county bought the tunnel from the CSX railroad company for $1. Some 13 years and $5.4 million later, the tunnel and entry trails opened, 19 years after the project was first conceived.

The dark, quiet environment is not totally devoid of wildlife. Songbirds such as eastern phoebes nest in the rocks, and state experts have identified three species of bats hibernating for the winter in the tunnel. Other observers have spotted long-tailed salamanders skittering about.

Many visitors carry flashlights and even lanterns as they venture into the tunnel – not only for navigation, but also to better understand the tunnel’s ecosystem and better ponder the history of this relic from Virginia’s past.

“There’s nothing quite like this in the country in terms of age, design, and the way it’s preserved,” said Hale, who is considered the “kingpin” of the Blue Ridge Tunnel path. “It’s perfectly preserved as in 1858 when the trains came through. Every time I’ve seen people there, they are having a good time.”

Glenda Booth is a freelance writer based in Virginia. She writes for publications around the state.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Head to the Nelson County’s online site for visitors to the Blue Ridge Tunnel at nelsoncounty.com/blue-ridge-tunnel or check out The Claudius Crozet Blue Ridge Tunnel Foundation at blueridgetunnel.org.